Analyzing School District Cash Reserves in Kansas

During the first few meetings of the Kansas Education Funding Task Force, both policymakers and district leaders have raised a familiar question: how much money are school districts keeping in reserve — and why?

It’s a fair question, with both practical and political implications. On one hand, maintaining healthy reserves is a typical method to manage risk, ensure cash flow, and plan for large expenses. One the other hand, visible fund balances often prompt scrutiny from those questioning whether schools are holding on to more than they need.

These cash reserves are often talked about in terms of encumbered and unencumbered cash balances. Although they both reflect unspent money, they function very differently:

- Encumbered balances are set aside for specific purposes because they are obligated for future payments.

- Unencumbered balances, in contrast, are not obliged to future payments and can be spent at any time, for any allowable purpose.

Another important distinction is between restricted versus unrestricted funds. State law has established 34 different funds, including contingency reserve (unrestricted) and special education (restricted). School districts can carry over balances in both types of funds, but restricted funds can only be spent on specified allowable uses under state law, depending on the fund.

A few years ago, the Legislative Post Audit Committee commissioned a report to investigate overall balances in Kansas school districts. The resulting report was published in November 2020 and offered a detailed look at how these balances have changed over time and how districts are using them.

This blog revisits that analysis, looks at updated school district data, and considers whether the findings of the previous audit still hold true today. In addition, it explores how state and local leaders may think about setting clearer expectations for district reserves in the long run.

Key findings from the audit

The report looked at data from school districts between 2009 and 2019. It set out to answer two questions: How have districts’ unencumbered cash balances changed over that time period and how have districts spent these balances? In addition to looking at raw data, the report also interviewed 25 districts to get a richer understanding of the use of funds.

Overall, the report found five key findings.

1. Total balances have grown, but mostly in restricted funds

Kansas school districts’ total unencumbered cash balances grew by 35% (adjusted for inflation), increasing from $1.56 billion to $2.11 billion. However, almost all this growth (96%) was concentrated in a small number of funds, most notably:

- Bond and interest funds used to pay off school construction bonds grew by $219 million.

- Contingency reserve funds used for unexpected expenses grew by $85 million.

These increases were reflective of rising construction costs and more cautious financial planning in the wake of the 2008 Great Recession, which brought subsequent delays in state K-12 funding.

2. Most reserves are in restricted funds

In 2019, 86% of all district cash balances were in restricted (encumbered) funds, meaning the money can only be spent for specific purposes (e.g., special education, food service, bond/debt service, etc.) limiting districts’ flexibility. The report notes the example of rising costs in special education could not be met with extra money in its bilingual fund, as the two cannot be cross applied.

3. Why districts carry cash balances

The audit identified four common reasons districts maintain reserves:

- Managing cash flow gaps like special education costs beginning in August, but funding arrives in October.

- Covering unexpected costs like HVAC repairs and snow removal.

- Saving for planned purchases like textbooks and routine building maintenance.

- Hedging against funding instability, such as recessionary periods and delayed or reduced state payments.

4. Spending suggests prudent use

Among the 25 interviewed districts, most unencumbered balances were put toward construction, maintenance, and ongoing operations costs — not simply stockpiled. More than 77% of reviewed spending went toward tangible district needs like HVAC systems, salaries, and land purchases.

5. No state standard for cash reserves

There is no statewide guidance for how much cash a district keeps on hand. The Government Finance Officers Association (GFOA) recommends maintaining at least two months of operating reserves. Among the 25 districts interviewed, 60% met or exceeded this benchmark, but amounts varied widely: from 37% to 200% of GFOA’s recommendation.

While KSDE does monitor balances and flag outliers, it provides little formal guidance. None of the districts interviewed had written policies about reserve targets at the time, but a few had informal goals or annual reviews during board meetings.

What does more recent data tell us?

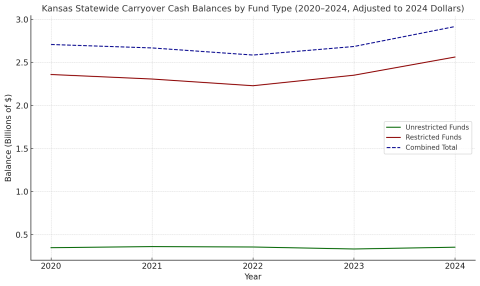

Looking at recent data (2020-2024) from KSDE confirms several of the previous audit’s key takeaways, but the pace of unencumbered balance growth has slowed in recent years.

Total balances continue to rise modestly

Between FY 2020 and 2024, total statewide carryover cash reserves grew from $2.71 billion to $2.92 billion, an increase of about 7.7% in real (inflation-adjusted) terms. Compared to the growth over the previous decade, when balances rose 35%, that is a much slower rate of growth.

While districts continue to maintain healthy reserves, the sharp growth we saw in the wake of the Great Recession has moderated.

Unrestricted balances have remained stable

Unrestricted funds, housed primarily in contingency reserve, general, or supplemental general funds, have held steady since 2020. In real terms, these balances increased from $348 million to $354 million in 2024.

Since 2020, districts have marginally expanded their unrestricted reserves, opting to maintain a consistent buffer to address risks or timing gaps.

Growth concentrated in bond, capital funds

Just as the previous audit found that bond and interest funds drove most of the reserve growth, recent years show the same trend continuing. Between 2020 and 2024, balances in bond and interest funds grew by more than $180 million, while capital outlay reserves also increased substantially.

These patterns reflect the continued cost pressures of maintaining and financing school facilities.

Understanding cash flow and timing

In a recent presentation to the Kansas State Board of Education, Dr. Frank Harwood, Deputy Commissioner at KSDE, offered additional context that helps provide further context around district cash balances.

Cash balances are reported on July 1, which is just the start of the school fiscal year. By that time, many districts have received much of their revenue but have not yet paid out major expenses for salaries, services, or materials. This timing can create the appearance of surpluses when in fact those funds are encumbered for near-term obligations.

Dr. Harwood noted that district cash balances fall into four broad categories:

- Capital funds (restricted), which are used for facilities and major equipment. These balances often exceed annual expenditures due to construction timelines and rising costs.

- Levied funds (some restricted, some unrestricted), which come from local property tax collections and are used to stabilize future levies or cover revenue losses from delinquent payments or tax appeals.

- Operational (some restricted, some unrestricted) funds, which cover the day-to-day costs of education. For FY 2024–25, the statewide reserve for operational funds sits at about 15.7% of revenues — roughly in line with GFOA recommendations.

- Special purpose (restricted) funds, which are restricted to specific uses under state or federal law.

One example of the cash flow challenge is the special education fund. Districts begin hiring staff and providing services in August, but the first state aid payment for special education doesn’t arrive until October. As a result, districts must carry sufficient balances forward to bridge that gap and ensure services continue without disruption.

This reinforces the importance of understanding the structure and timing of school finance before drawing conclusions based solely on end-of-year balance sheets.

Rethinking reserves

As Kansas policymakers think about school district cash balances, it’s worth noting that the GFOA has its guidance on reserve management. In a 2023 report, Should We Rethink Reserves?, GFOA encourages governments to move away from fixed rules and toward flexible, risk-based strategies.

Here are a few considerations to keep in mind as this conversation continues:

- One size doesn’t necessarily fit all. If the state wants to issue guidance, consider ranges (1.5 – 3 months) instead of ridged 2-month mandates. Districts face different risks, be they fiscal, operational, and/or environmental. A flat reserve target may not reflect local needs or risk tolerance.

- Transparency helps. Requirements to disclose reserve strategies at local board meetings could alleviate broader concern. Cleaner explanations as to why reserves exist and how they will be used can ease political pressure and improve public trust.

- Excess balances do not need to sit idle. If reserves exceed a district’s risk-based target, some funds might be used for on-time investments or to reduce total liabilities.

- Provide tools or technical assistance. Some districts may need help conducting risk assessments or to create reserve policies, especially smaller districts with less capacity.

Ultimately, potential reserve policies should strike a balance between financial stewardship and responsiveness to actual needs. Many Kansas school districts seem to be walking that line carefully, with the data showing that the conversation is still worth having in areas of the state.