A Brief History of Literacy Instruction in America

This post is the second in a series exploring literacy within education policy and practice. In the first blog, we introduced the major methods of teaching reading in the U.S. — phonics, whole language, balanced literacy, and sight word memorization. Here, we look at how those methods developed and why the debate over reading instruction has proven so persistent.

Understanding that history helps explain why today’s renewed focus on the science of reading has emerged — setting up our next post, which will examine the data and policy evidence showing why explicit, systematic reading instruction produces the best results for students.

The history of literacy instruction in America can be thought of as a series of pendulum swings, each grounded in a different philosophical theory of learning. At each turn, these theories were motivated by real concerns about how children learn and translated into increasingly coherent instructional practices.

Broadly, the story begins with the back-and-forth between behaviorism and constructivism, as policymakers and educators debated whether reading should be taught through structured drills versus natural discovery. The next phase commenced the so-called “reading wars,” a period of intense debate about research and practice that tried, unsuccessfully, to resolve itself through a pragmatic middle ground. Finally, and most consequentially, the rise of cognitive science brought a new focus and growing consensus on evidence-based instruction — though applied slowly and unevenly across classrooms.

Early literacy instruction

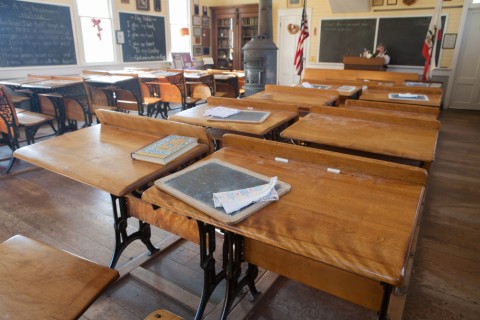

While public schools began to take shape during the colonial period, the 1800s saw the rise of the Free Public School movement championed by activists like Horace Mann that culminated in mandatory education for all children in the early 1900s. This social and political movement emphasized order and discipline among students, which was reflected in the instructional materials of the day.

If you attended school during this time, there was a good chance you were taught to read and write using a textbook known as a McGuffey Reader. Created by an academic and educational advocate William Holmes McGuffey, an estimated 120 million McGuffey Readers were sold between 1836 and 1960 (only behind the Bible and Webster’s Dictionary).

McGuffey and his Readers employed what was then known as the alphabet method, or a version of modern-day phonics instruction, to develop students’ technical reading and writing skills. These books encouraged students to sound words out and read aloud to their classmates. Overall, the idea was to see literacy as a skill taught gradually according to grade levels.

The idea that children learn step-by-step in a drill-based way reflected an early form of what scholars would later term behaviorism, a theory of learning that focused on practice, repetition, and reinforcement. Behaviorists thought students learn best when skills are broken down into small, digestible parts, taught directly, and mastered through routine. Though the term would not be formalized until the early 20th century, the logic underlying behaviorism was already present in classrooms using McGuffey Readers.

It would be a mistake to think widespread phonics drilling of this era brought consensus. Indeed, Horace Mann — then secretary of the Massachusetts Board of Education — argued against phonics-based instruction, calling it mechanical and uninspiring for students. Mann favored instead a version closer to whole-word learning, where children absorbed meaning from text and not labor through sounds and syllables.

In 1886, psychologist James Cattell added empirical weight to these critiques. Studying eye movements, he found that adults recognized letters more accurately and quickly when they appear within a whole word than in isolation. Cattell concluded that readers process words more efficiently as complete units, a finding that gave early support to whole-word instruction.

By the 1920s and 30s, dissatisfaction with phonics drills was widespread, and the ideas advanced by Mann and Cattell were back in vogue. Instead of letter-by-letter decoding, educators promoted the recognition of entire words by their general pattern, distinctive features, or similarity to known words. When this was insufficient, students were encouraged to rely on illustrations or sentence context, making educated guesses to construct meaning.

This “look-say” approach was made popular by textbooks like the Dick and Jane series, which repeated simple phrases supported by pictures. Students memorized words by sight and used context to fill in the gaps, reflecting the belief that reading, like speaking, could be acquired naturally through exposure. By mid-century, this philosophy had gained wide traction in American classrooms.

At its heart, this method reflected a constructivist theory of education — that children build knowledge through experience, exploration, and making meaning, rather than through drills alone. Students would have to actively build (i.e., construct) knowledge, not passively absorb it, to maintain motivation and gain fluency.

While this method is appealing for its simplicity and focus on the child, over time it started to draw fierce criticism.

In 1955, Rudolf Flesch published a seminal and bestselling book Why Johnny Can’t Read, which directly attacked the “look-say” method. Flesch argued that the abandonment of phonics drilling left American students unprepared. He presented evidence suggesting that many students were struggling to pronounce and understand unfamiliar words since they were never taught the relationship between sounds and symbols. Flesch’s book foreshadowed an increasingly confrontational period between advocates of phonics and whole language instruction.

The reading wars

The growing divide between phonics and whole-word instruction sharpened in the decades that followed. In 1967, Harvard researcher Jeanne Chall published Learning to Read: The Great Debate, a landmark analysis of more than 100 studies on reading instruction.

Her conclusion was clear: children who received systematic phonics instruction developed stronger early reading skills than those taught through whole-word or meaning-first approaches, particularly students who struggled with reading or came from disadvantaged backgrounds.

That same year, researchers Guy Bond and Robert Dykstra released the First-Grade Studies, one of the most comprehensive investigations of reading methods ever conducted. Their work tested multiple instructional models in more than 200 classrooms across the country. The results reinforced Chall’s conclusion: phonics-based instruction consistently produced stronger outcomes in early literacy.

These findings, however, did not end the debate. Many educators, influenced by emerging ideas about child development and meaning making, viewed reading as a natural process that should not be reduced to drills. Scholars such as Kenneth Goodman and Frank Smith argued that proficient readers rely on context and prediction as much as decoding, framing reading as a “psycholinguistic guessing game.”

By the 1980s, whole language approaches emphasizing authentic literature and student choice had become dominant in teacher training programs. Meanwhile, phonics advocates continued to point to decades of empirical research showing that explicit instruction in sound-symbol relationships remained essential for many learners.

The term “reading wars” emerged to describe this growing divide between research and practice. Academic journals, professional associations, and popular media all weighed in. While the debate was often presented as a struggle between competing camps, most educators agreed on the underlying goal of helping students become fluent, confident readers who understood what they read.

Still, the field lacked consensus about how best to achieve that goal — a tension that would eventually lead to the next major development in literacy instruction.

Balanced literacy: A pragmatic middle ground?

By the 1990s, many educators and administrators were eager to move beyond the long-standing debate over phonics and whole language. A new approach — balanced literacy — emerged as an attempt to combine the strengths of both philosophies. In theory, it offered the best of both worlds: explicit instruction in foundational skills alongside meaningful engagement with literature.

Balanced literacy programs typically included three recurring elements:

- First was the three-cueing system, which encouraged students to use context clues, sentence structure, and pictures to identify unfamiliar words.

- Second was independent reading time, during which students selected books at their own interest and skill levels to build motivation and fluency.

- Third was the use of leveled readers, assigning students texts labeled by difficulty and gradually increasing complexity as they improved.

For many teachers, balanced literacy felt both flexible and intuitive. It allowed for structured lessons in phonics and decoding during independent reading time while maintaining time for student choice and authentic reading experiences. The approach became deeply embedded in schools of education, district curricula, and widely used instructional materials.

Over time, however, questions emerged about its effectiveness. Research found that cueing systems often encouraged guessing rather than decoding and that assigning students to easier texts sometimes limited exposure to grade-level vocabulary and syntax. Critics argued that while balanced literacy aimed to blend explicit and implicit methods, in practice it often underemphasized systematic phonics instruction — the very component shown to benefit struggling readers the most.

By the early 2000s, the need for a more evidence-based and comprehensive model of literacy instruction had become clear. This set the stage for the rise of cognitive science and the modern science of reading movement, which sought to ground classroom practice in decades of research about how children actually learn to read.

The rise of cognitive science and the science of reading

At the turn of the 21st century, advances in cognitive psychology and neuroscience began to reshape how researchers and educators understood reading. These fields revealed that, unlike spoken language, reading is not an innate human skill — it must be explicitly taught through systematic instruction that connects sounds to letters and letters to meaning.

In 2000, the National Reading Panel synthesized decades of research and identified five essential components of effective reading instruction:

- Phonemic awareness – understanding and manipulating individual sounds in spoken language.

- Phonics – connecting those sounds to written letters and spelling patterns.

- Fluency – reading accurately, quickly, and with expression.

- Vocabulary – knowing and using a wide range of words.

- Comprehension – constructing meaning from text.

Later work added background knowledge as a sixth foundational component, emphasizing that understanding a text depends on what the reader already knows. Together, these findings formed the basis of what came to be called the science of reading — a body of interdisciplinary research grounded in evidence from linguistics, psychology, and education.

In 2018, journalist Emily Hanford helped bring this research to national attention through her widely circulated reporting Hard Words: Why American Kids Aren’t Being Taught to Read. Her report revealed that many teacher preparation programs and districts were still using methods derived from whole language and balanced literacy, even as evidence pointed toward more systematic phonics.

The national conversation that followed prompted sweeping state action. According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, 38 states and Washington, D.C. have enacted laws or policies aligned with the science of reading, requiring evidence-based curricula, teacher training, or early intervention. These efforts mark one of the most significant literacy reform movements in decades.

While implementation remains uneven, the trend reflects a broader shift: literacy policy today is increasingly grounded in research rather than ideology. Yet as history shows, translating evidence into consistent practice takes time.

Onward to action

The history of literacy instruction reveals a long struggle to balance structure and meaning in how children learn to read and write.

From McGuffey Readers to balanced literacy, each generation of educators has sought the right formula for teaching children to read. Yet the evidence accumulated over the last several decades points toward a clear conclusion: structured, evidence-based instruction provides the most reliable path to literacy for all students.

Today’s challenge is not choosing between sides but integrating what we know works. The most effective classrooms combine explicit phonics instruction with rich opportunities to develop vocabulary and background knowledge to enable comprehension. Reading and writing are not only skills to be taught but also experiences to be cultivated, as they enrich our understanding and connection with the world.

In our next post, we will dig into that evidence, exploring what recent test results, studies, and state policies show about what works — and how Kansas and Missouri fit into this national movement.