A Closer Look at Early Literacy in Kansas and Missouri

This post continues our series on literacy policy and practice. Earlier entries traced how reading instruction evolved in the U.S. and why the science of reading has regained prominence.

Here, we turn to what the data shows in Kansas and Missouri—and why both states have stepped up efforts to improve early reading. We’re also releasing a new K–3 Literacy Policy Brief that brings together the major reforms underway and outlines practical steps for strengthening outcomes.

Third grade reading remains a critical checkpoint in early education. Students who are not proficient by this point are significantly more likely to struggle with comprehension, fall behind in later grades, and face a host of negative life outcomes after high school.

In Kansas and Missouri, the data paints a consistent picture: early literacy is not where it needs to be, and progress remains too slow.

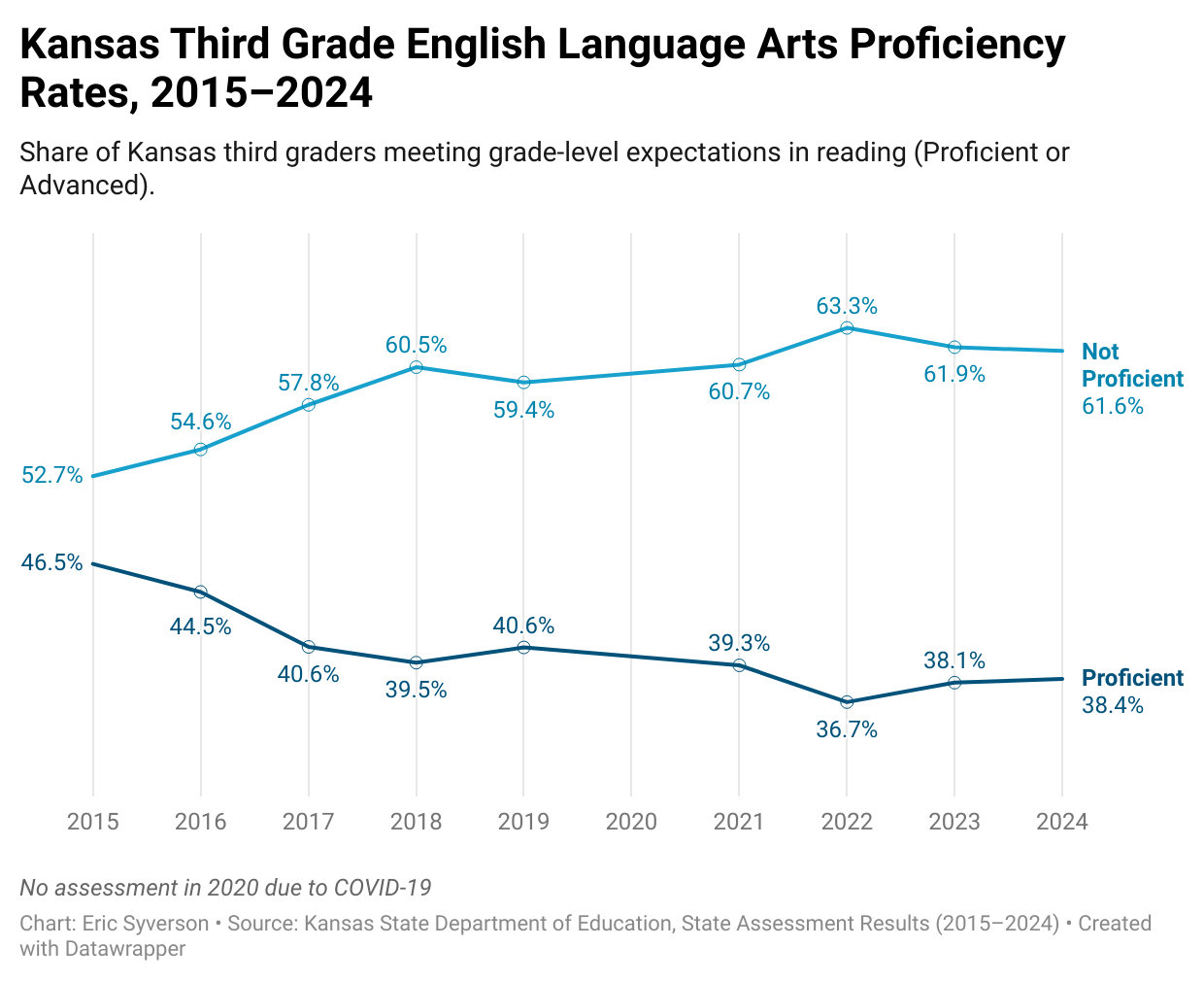

In Kansas, third-grade ELA proficiency has declined gradually over the past decade. In 2015, 46.5% of students scored Proficient or Advanced. By 2024, that number had fallen to 38.4%, meaning roughly six in ten Kansas third graders are not reading at grade level. The trend moved slightly up or down in individual years, but the overall direction has been a steady erosion of early reading performance.

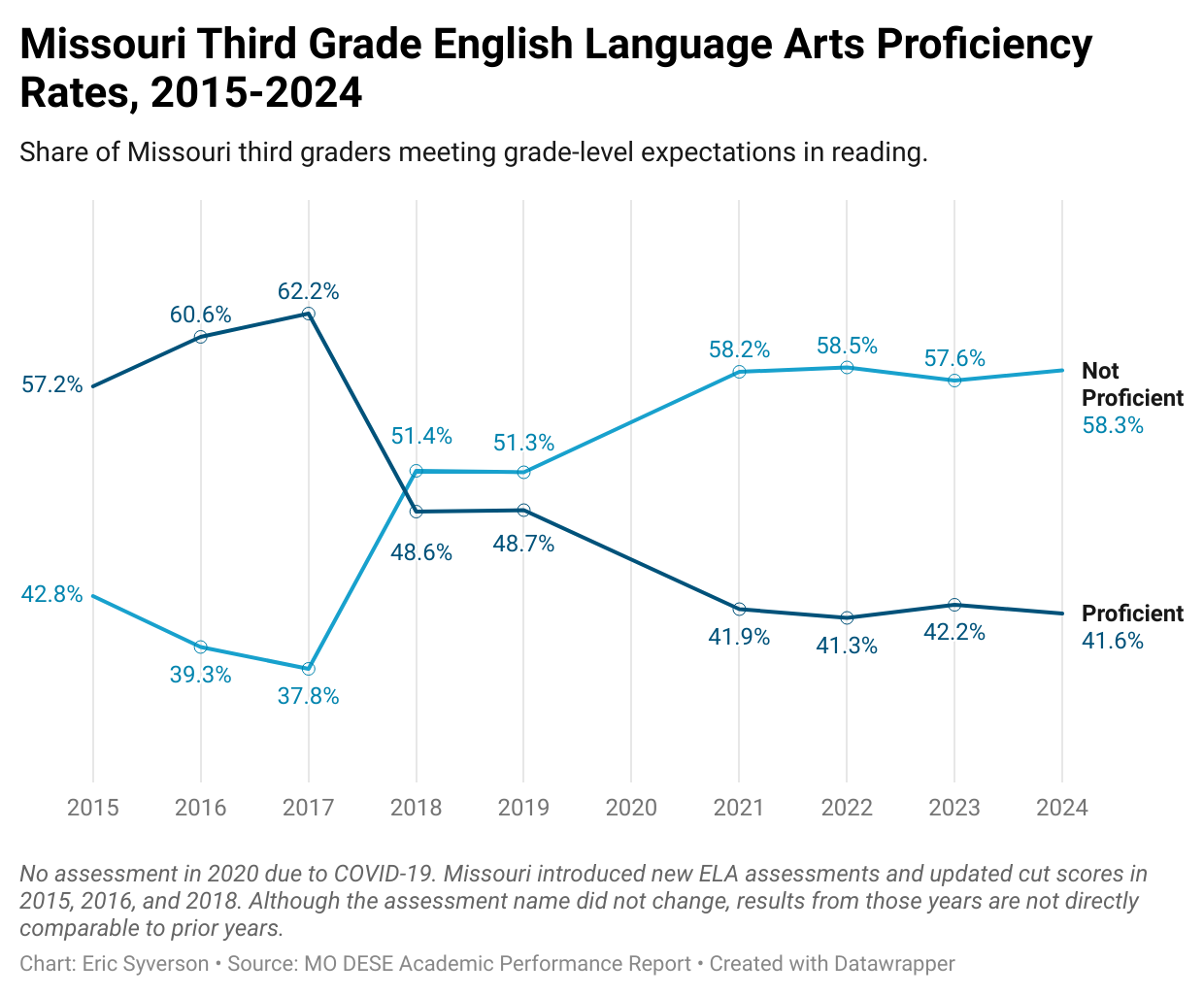

Missouri’s results show a different pattern but lead to a similar conclusion. Since 2018, third-grade proficiency has hovered around 40–42%, with the most recent year at 41.6%. The most recent results show that 58% of Missouri third graders are not meeting grade-level expectations. Several assessment changes over the past decade make long-term comparisons difficult, but the last six years of stable test design show little movement in either direction.

Both states share another common thread: early reading challenges tend to persist as students move through school. Once gaps open in kindergarten through third grade, it becomes increasingly difficult for students to catch up. This makes early literacy not just an instructional issue, but a systemic one that shapes everything.

These results underline why Kansas and Missouri have invested so much energy in improving reading instruction: the status quo was not producing the outcomes students need. And while both states have taken meaningful steps, the work ahead remains substantial.

State action takes center stage

Policymakers in both states have spent the last several years reshaping the foundation of early literacy. Both states have adopted policies that align more closely with research on how children learn to read, and both have made significant changes in teacher preparation, curriculum, and early intervention.

Kansas has strengthened teacher preparation, banned three-cueing, created a statewide Office of Literacy, expanded regional reading centers, and required structured-literacy materials beginning in 2025. Universal K–3 screening, tiered supports, and annual progress reporting are now in statute, shifting the state toward earlier identification, explicit instruction, and more consistent intervention.

Missouri has taken a similar route by adopting universal dyslexia screening, creating Reading Success Plans, investing in LETRS training, prohibiting three-cueing, and aligning teacher preparation to structured literacy. The Read, Lead, Exceed initiative and renewed CLSD funding have expanded coaching, curriculum support, and district implementation, building a stronger statewide framework for early prevention and intervention.

Our new K–3 Literacy Policy Brief pulls these developments together into one resource. It outlines:

- How Kansas and Missouri approach prevention, intervention, and retention.

- Where their statutory requirements align with national best practices.

- A decade of major literacy laws and initiatives in each state; and,

- Practical policy considerations that can accelerate progress.

The brief’s core takeaway is straightforward: both states have settled the “what” of early literacy reform: science-aligned instruction, high-quality materials, universal screening, and early reading plans. The challenge now is the “how”: consistent, high-quality implementation in classrooms, supported by coaching, progress monitoring, and clear expectations for intervention time.

States that have improved reading quickly show the importance of execution and state support of school districts. Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee did not wait for policies to mature over a decade; they paired strong laws with hands-on implementation support, teacher coaching, simple progress checks, and transparency about whether students received the help they needed.

Moving forward as a region

If Kansas and Missouri want stronger fourth-grade reading, stronger high school readiness, and a stronger workforce pipeline, the path runs directly through early literacy.

The data is clear: too many students are starting behind and staying behind. Policy changes over the last several years have laid essential groundwork, but turning those policies into measurable gains will require steady follow-through and attention — screening on time, delivering real intervention minutes each week, supporting teachers, and giving families clear information.

States across the country have shown that improvement is possible, and often faster than expected. Kansas and Missouri are now positioned to join them.

Our new literacy policy brief offers the roadmap. The next step is collective action to ensure every student in the region learns to read so that they may read to learn.